Holly: Veteran, Athlete, Inspiration

Posted By PVA Admin on March 9, 2018The Real G.I. Jane, this former U.S. Army captain, a T7 para, could teach Demi Moore and the rest of Hollywood a thing or two about courage.

Pictured: Holly with her service dog in 2017.

“What’s it like to be in a wheelchair?” “How fast can you go?” “Will you ever walk again?”

Fifth graders at Pleasant View Elementary School, in Parma, Ohio, crowd eagerly around their new student teacher, Holly. The 37-year-old former U.S. Army captain, a T7 para, fields their questions like a well-seasoned instructor. She’s not worried about surviving her last semester at Cleveland University in pursuit of an education degree.

“Teaching kids is a lot like being a military officer,” she says, “When I took charge of a maintenance company, my battalion commander was kind leery of the situation. I was only five feet, three inches and soft-spoken. But once I showed my troops I could do my job, we had an understanding. I treated them with respect, and they respected me. We had one of the best companies in the 101st Airborne Division at Fort Campbell, Ky.”

Holly doesn’t like to boast about her many accomplishments; in fact, she wondered why PN/Paraplegic News would want to do an article about her. “I’m not special” she insists. “I just go out there and give it my all every day.”

‘I’m not special” she insists. “I just go out there and give it my all every day.’

________________________________

A Study in Courage

Anyone who has seen Holly at the National Veteran Wheelchair Games (NVWG) would argue with her modest self-appraisal. A study in courage and an inspiration to everyone she meets, she exudes positive attitude that creates grins and lifts spirits.

Holly grew up in Buffalo in a family of five children. She and her twin sister, Joy, were always close. She says, “One time we traded identities – I took a pop quiz for Joy and failed it. After my Dad went to school to explain what we had done, we were careful not to push it too far.”

Holly and Joy wanted to join the Army after high school, but their father insisted they go to college first. “In our junior year at Fredonia State [N.Y.],” says Holly, “we saw some ROTC guys rappelling off the school’s towers. We were so impressed we signed up for a couple of courses. Before we knew it, we had scholarships for the last two years of college. When we graduated, we were commissioned into the Army as second lieutenants.

The Army has changed since Holly and Joy went through basic training, which included white-glove inspections and tough drill instructors [Dis]. She says, “I talked to one newly injured veteran who told me if recruits feel like they’re being harassed or mistreated, they can hand out ‘stress cards’ to their Dis, who are required to take it easy on the charges. And, of course, now the infantry does PT [physical training] in sneakers instead of boots.”

Holly went to ordinance school at Aberdeen Proving Ground (Md.) and Joy, a quartermaster, to a base in Fort Lee, Va. A few months later the twins ended up in Germany. Holly says, “We hoped to get assignments in the same country, but we never expected to end up right across the street from each other in Nuremberg. Somebody must have seen the two matching last names names and thought it would be funny to put us together in the same city. When our soldiers would see one of us, they would salute and ask, ‘Are you my ma’am or the other ma’am?’”

The twins’ next assignment turned out to be bases in Kentucky – Holly at Fort Campbell and Joy two hours away at Fort Knox. “I was into air assault,” says Holly. At Fort Campbell I learned about moving equipment – artillery pieces, small howitzers, and Jeeps. It involves rappelling out of helicopters.”

In a stint at an Ogden, Utah, army base, Holly served as a liaison between arms producers and the troops using the weapons. Her specialty was the Tow II missile system. Now she was ready for the big picture.

________________________________

The Turning Point

In Huntsville, Ala., Holly was involved in the initial stages of gearing up for Operation Desert Shield/Storm. “This was before the military even had the name ‘Desert Storm,’ when the Army was training the first units to go over to Kuwait,” she recalls. “On August 11, 1990, the base was on alert, and I was driving down this dimly lit back road to get to the post. The next thing I knew, I woke up three days later in a Huntsville hospital. I had rolled my Bronco II two times.

She paused before she continues, “I’ve read witnesses’ reports of what happened because I don’t remember anything about that night. I was only traveling 35 mph – no skid marks – on what looked like a normal curve in the road. Joy and some of my friends went to the site later and couldn’t believe an accident occurred there, but when they watched top-heavy vehicles trying to negotiate the curve, they noticed many of the trucks taking it on two wheels. I guess this section had not been graded properly.”

Holly’s vertebra was crushed at the T7 level. Her mother and younger sister, KC, rushed to Huntsville to be by her side, and her dad and brothers followed. Army friends traveled from everywhere to visit her in the next few days. Hospital staff plastered the walls of her room with cards and letters, and she received flowers from former battalion commanders. Holly says, “The military is a family, and my fellow soldiers proved that to me.

“After my accident, hospital staff rigged me up in a Stryker frame – I was so uncomfortable hanging face down with all those straps. Nurses flipped me every four hours so I wouldn’t get pressure sores. I couldn’t eat anything or sit up, and sleeping was almost impossible.

I still remember my mother, who crawled on the floor underneath me when I was in that awful contraption. She had packed in such a hurry when she got the news about my injury that she forgot to bring any slacks. In her best dress, she would lie on that cold linoleum and talk softly to me until I fell asleep, I’ll never forget that.”

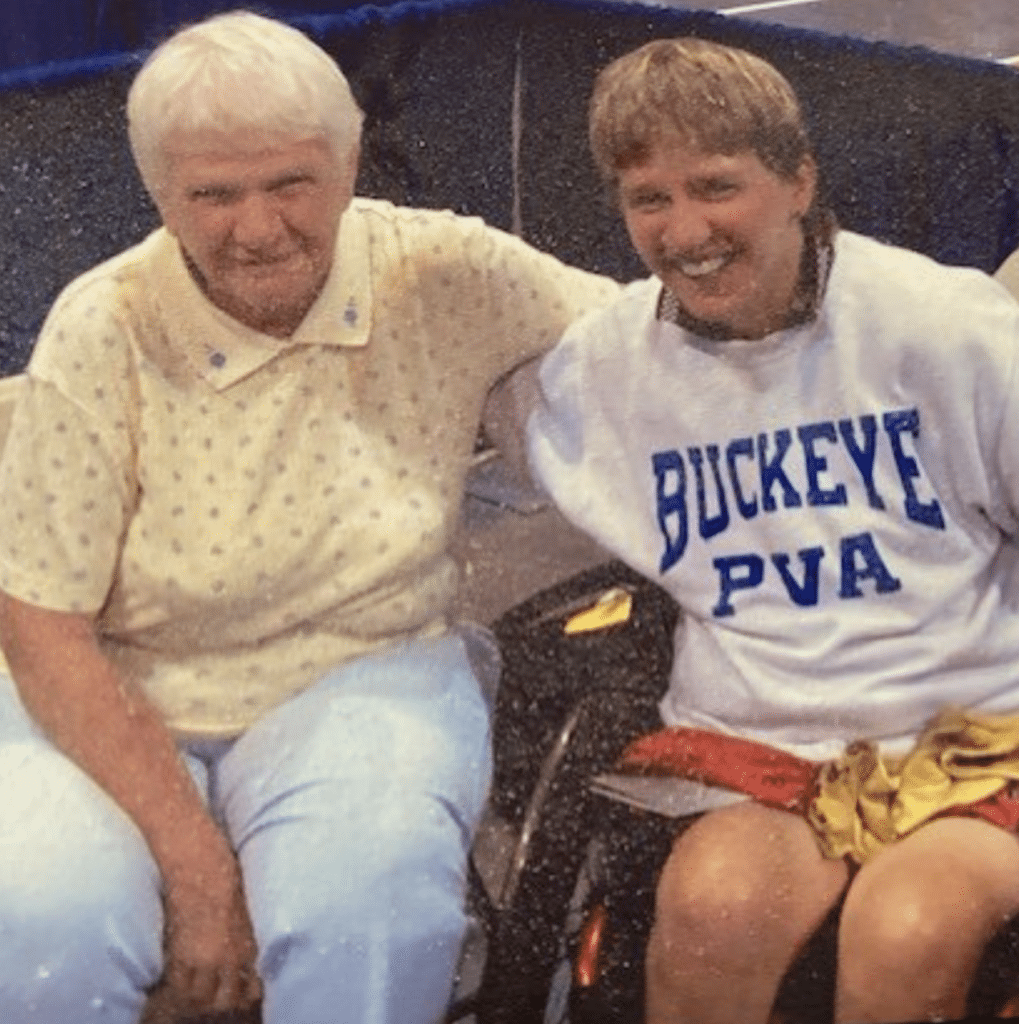

Pictured: Holly with her mother, Joan.

________________________________

On The Road to Recovery

Next stop: the Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center for rehab. “When my doctor told me I was going to a VA hospital, I cried,” says Holly. “I had just seen Born on the Fourth of July and was convinced I would live the same nightmare as Tom Cruise did in the movie if I went to one of these medical centers. My first night there, a man rolled in and started talking to me like we were old buddies. I couldn’t see his face, because I was still in the Stryker frame. Scott Law, who had been injured five years, said he was in a wheelchair, but he was completely independent. He had a house and even a swimming pool; VA and Paralyzed Veterans of America took good care of him.

“Well, that was the beginning of my relationship with PVA – another family I joined – and my life has never been the same. This organization has done so much to educate everyone about people with disabilities. I can’t say enough about the Buckeye Chapter and all the other members of PVA. I enjoy working as the chapter’s sports director encouraging other veterans to try all the new recreational activities that are out there for people with disabilities. This summer I water-skied, the first time I’ve been up on skis since my accident. It was awesome!”

Holly remembers another veteran who made a difference in her life. Tim Hodge, the guy in the next room at the Cleveland VAMC, was my hero. A quad, he could only move his chin, but he’d come in and ram my bed with his power chair and cheerfully shout, ‘Get out of bed, Captain.’ And since I still wasn’t strong enough to push my wheelchair, he was always happy to give me a tow. I realized that my situation was not so bad. And I decided I’m gonna do everything I can with what I have. Now there’s nothing I can’t do – except walk.

Holly’s first attempt at the NVWG was in 1991 in Miami. “Participating in the Games was Melvin Blackwell’s idea; he was my physical therapy coach,” she says. “He wanted to show me I didn’t have to sit on the sidelines. I signed up for the slalom, even though I didn’t know how to ‘pop a wheelie.’ When I fell out of my chair, I was disqualified, so I begged the referee to give me one more chance. I really had to struggle to finish, but I heard my family and friends cheering me on. That day I understood the main thing is to get through it – whatever “it” is. And ever since then, the NVWG rule is that wheelers who take spills in their chairs in the slalom get a penalty; they are not disqualified.”

Holly received the Endeavor Award from the British team for her efforts in Miami. In 1996, she took home the Spirit of the Games Award. In San Diego, she watched a veteran, a newly injured novice, push the 5000m in an everyday chair. She says, “It took a lot of guts for him to get out there. Next time he’ll be in a racing chair and cutting his time in half. That’s what the Games are all about. Seeing what other guys can accomplish is what makes me know what I can do.”

One of the things Holly can do is teach. She remembers a practicum she completed as part of her education credits – in an elementary school with a library upstairs and no elevator. The lunchroom and gym were located on the floor below. No one seemed to be too concerned about the barriers she encountered as a wheeler. In her final semester as a student teacher, she is relieved to be learning her craft in an accessible school, built on one level. “Inclusion is strongly stressed here,” she says. “I’m tutoring a girl who is visually impaired, but she is in the regular classroom. She uses a Braille typewriter to complete her assignments and tests.”

Holly plays videotaped NVWG highlights to show her students what people in wheelchairs can do. “After we watch the video,” she says, “we all write about role models and heroes…”

“I tell the kids they can do anything if they work hard enough. There are no obstacles they can’t overcome.”

Original article courtesy of PN Magazine.